I've always wanted to build a living, breathing site with Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment tools -- and blog about it. So why not build the blog website itself? Here are the main elements of the CI/CD process:

Source Control Stored In Github

https://github.com/JamesQMurphy/www-jamesqmurphy-com

When it comes to source control for a public project, GitHub is still the obvious choice. My branching strategy is more-or-less GitHub Flow:

- Create a feature branch named

features\new-feature. - Update the version number in

azure-pipelines.yml(see my post on build numbering). - Make changes on the new branch and commit.

- When testing is needed, manually trigger a build of the feature branch, which gets automatically deployed to the DEV environment.

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 as needed.

- When ready to commit, open a pull request against the

masterbranch. - After reviewing, merge the pull request to

master, which automatically triggers the production build, which in turn triggers a production release. - The production release gets automatically deployed to the STAGING environment and waits for my approval before deploying to production. After reviewing the changes in STAGING, I approve the release to production.

Sometimes, if I'm working on a bigger, long-running release, I'll create a branch named releases\X.Y.Z to serve as an intermediate

checkpoint. Pushes to release branches automatically trigger builds which are deployed to DEV.

Built and Deployed By Azure DevOps Services

https://dev.azure.com/jamesqmurphy/www-jamesqmurphy-com

The build tools available with Azure DevOps Services are excellent -- and essentially free for

public projects. Builds are automatically triggered when commits are pushed to either the

master branch or a branch that starts with releases/. However, any branch can be built

by manually triggering a build from within Azure DevOps Services. Since it is a public project,

you can see the builds here.

I also have an Azure DevOps Release Pipeline named Deploy to AWS. Every build, except for pull-request builds, will trigger this pipeline. If

the build is triggered by a commit on the master branch, then the pipeline deploys to the STAGING and Production environments; otherwise,

it deploys to the DEV environment.

Hosted On Amazon Web Services

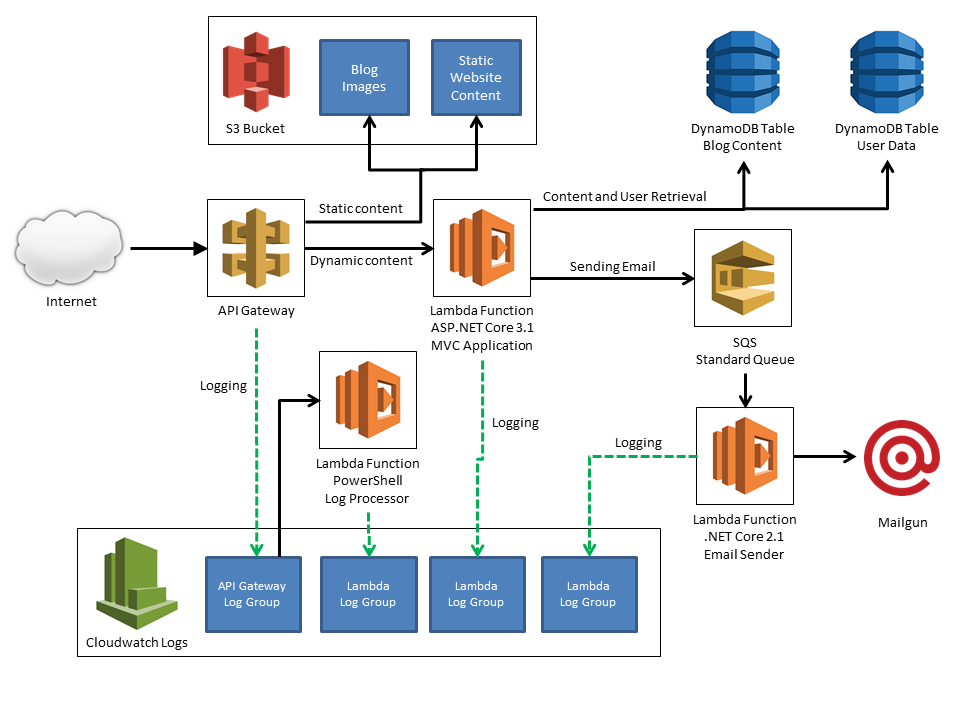

The website is hosted on AWS, and takes advantage of several AWS services:

At its center, the website is an ASP.NET Core 3.1 MVC application, hosted inside an AWS Lambda Function and exposed to the outside world via AWS API Gateway. Requests for static content, such as images, style sheets, and JavaScript files, are forwarded to AWS S3. The site uses AWS DynamoDB for data storage. For email, I use an AWS SQS Queue so that email errors don't cause an exeception in the website.

To actually send email, I use a third-party provider called Mailgun. I highly recommend them.

About Me

I'm JamesQMurphy and I've been doing DevOps since before they've been calling it DevOps -- which isn't that long ago. I've loved coding since I was eleven years old, but I also developed a love of the process of creating software. It's also part of why I studied Chemical Engineering at college; the two disciplines do share a connection when it comes to process.

My first real software job was working on a shrink-wrapped software package, as part of a team of four developers. This was way back in 1995, so Windows 3.1 was still the primary operating system of the day (most organizations didn't adopt Windows 95 until the next couple of years). In addition to writing the software package's calculation engine, I also developed the installation package (using Wyse) and helped introduce version control (Visual SourceSafe) to the team. I was the one who built the software -- always taking the latest version from SourceSafe, and always using the same batch file -- before creating the installation package and handing the diskettes to my manager, who inserted them into his diskette duplicating machine. (It even printed the labels!) Since those days, I've worked at many different types of companies, in all sorts of industries, but I always gravitated to the "build and release" side of things, mostly because it was a chance to relive my chemical engineering days by building a "software factory".

I think I first became aware of the "DevOps" term when I was Googling for stories between developers and operations. At the time, I worked for a software-as-a-service company, and relations between the development and the operations teams were strained, to say the least. The developers always claimed that the operations team "messed things up", and the Ops guys constantly complained about the developers blaming all of the software problems on them. (And they both had a point, for what it was worth.) By some ironic twist of fate, I was relocated into the same part of the office as the ops team, and I got to know them. I also started to overhear some of their conversations, and before long, I started to see things from their point of view. I asked questions. I listened. I learned.

It wasn't long before I became a sort-of emissary between the development and the operations team. When the developers asked me to troubleshoot a "network connection problem," I would actually strive to figure out if it was a DNS resolution problem or a routing problem. The ops guys, who were used to hearing things like "I'm getting a connection error, please advise," were much more receptive to questions like, "When I run NSLOOKUP I get this IP address; but I thought it was this IP address?"

I had become a DevOps engineer, although I didn't know that's what it was called.